For the next iteration of its Chicago Works series, the Museum of Contemporary Art presents the first solo museum exhibition of artist Maryam Taghavi (b. Tehran, Iran; based in Chicago, IL).

Taghavi’s practice insists on positionality: where one stands determines what—and how—one sees. For the past several years, her work with talismans, calligraphy, and the Islamic occult has coalesced into a series of sculptures and paintings that strive to signify the unseen. In her upcoming MCA exhibition, Taghavi creates new works that expand her interest in perception by interrogating the space between the illusive vanishing point of the horizon and the immutability of distance.

Taghavi’s exhibition will take over the MCA’s Turner Gallery on the fourth floor, culminating in an immersive installation that invites audiences to close one eye and peer with the other, to adjust their gaze to new spatial possibilities, and to imagine a relationship with what is imperceptible.

Link to the Exhibition Page

Text by Curator Bana Kattan:

Maryam Taghavi and a Choreography for Nothing

BANA KATTAN

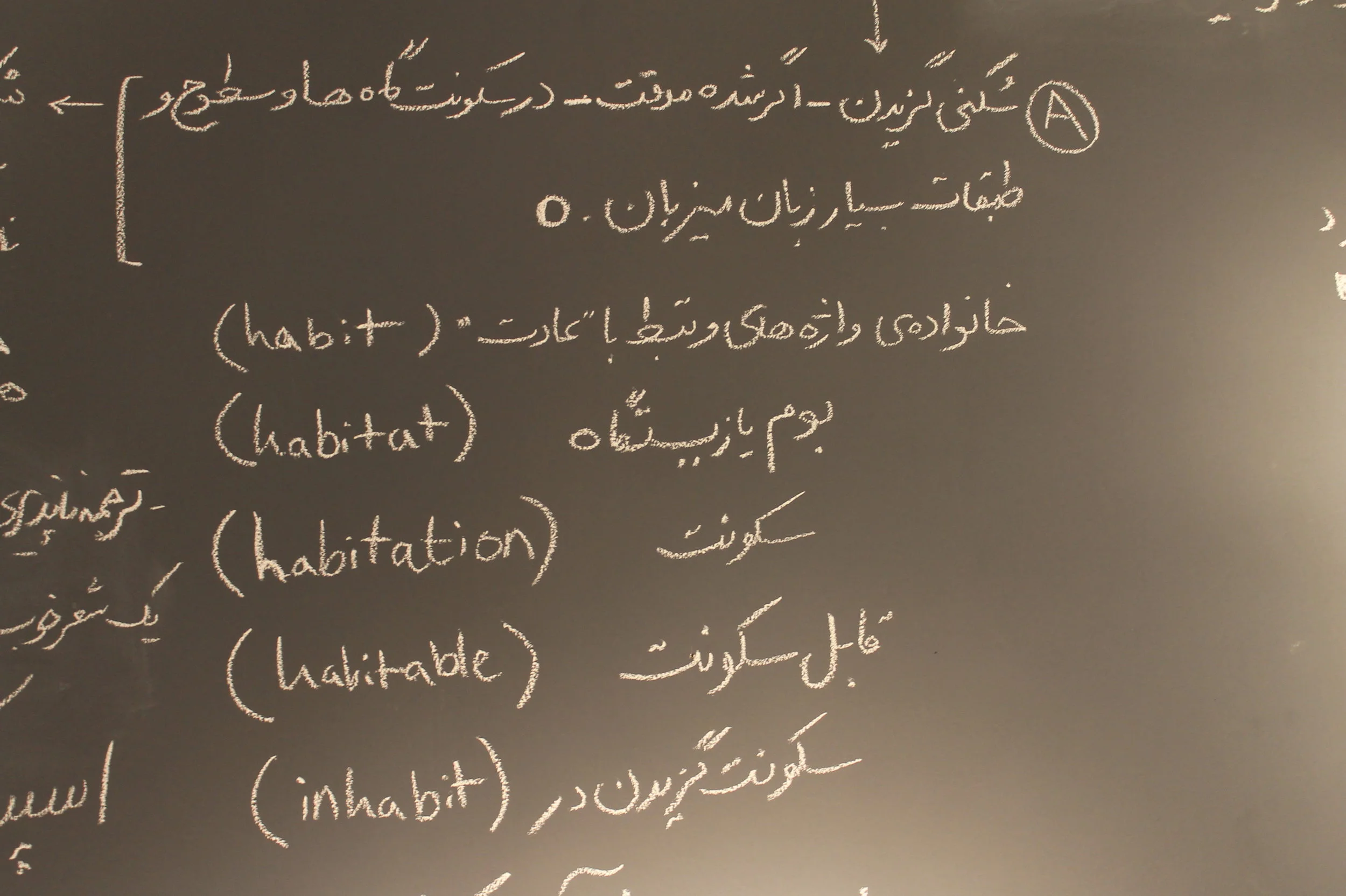

In Persian and Arabic, the noghte is the most essential diacritical mark. The number of noghte(s) that a writer places above or under a particular letterform indicates its sound: for example, the same letterform may become b, y, p, n, t, or th, depending on the noghte’s arrangement. Loosely translated into English as “dot” or “point,” in calligraphy this diacritic is etched from the slanted nib of a reed pen, creating a diamond-like form. In the early tenth century, a vizier to the Abbasid caliphs in modern-day Baghdad named Ibn Muqla developed a system for determining the size of letters in an alphabet based on the noghte. Muqla began by calculating the height of the first letter in the Arabic alphabet, the alif, based on the height of a series of noghte(s); he then determined the size of all other letters in relation to the alif[1]. Since Muqla’s invention of this “proportional script,” the noghte has been used as a unit of measurement for all spatial relations within a given calligraphic composition (fig. 1).

Figure 1. A 19th-century lithograph of script in the Naskh style, one of the earliest forms of Islamic calligraphy. Courtesy of Borna Izadpanah.

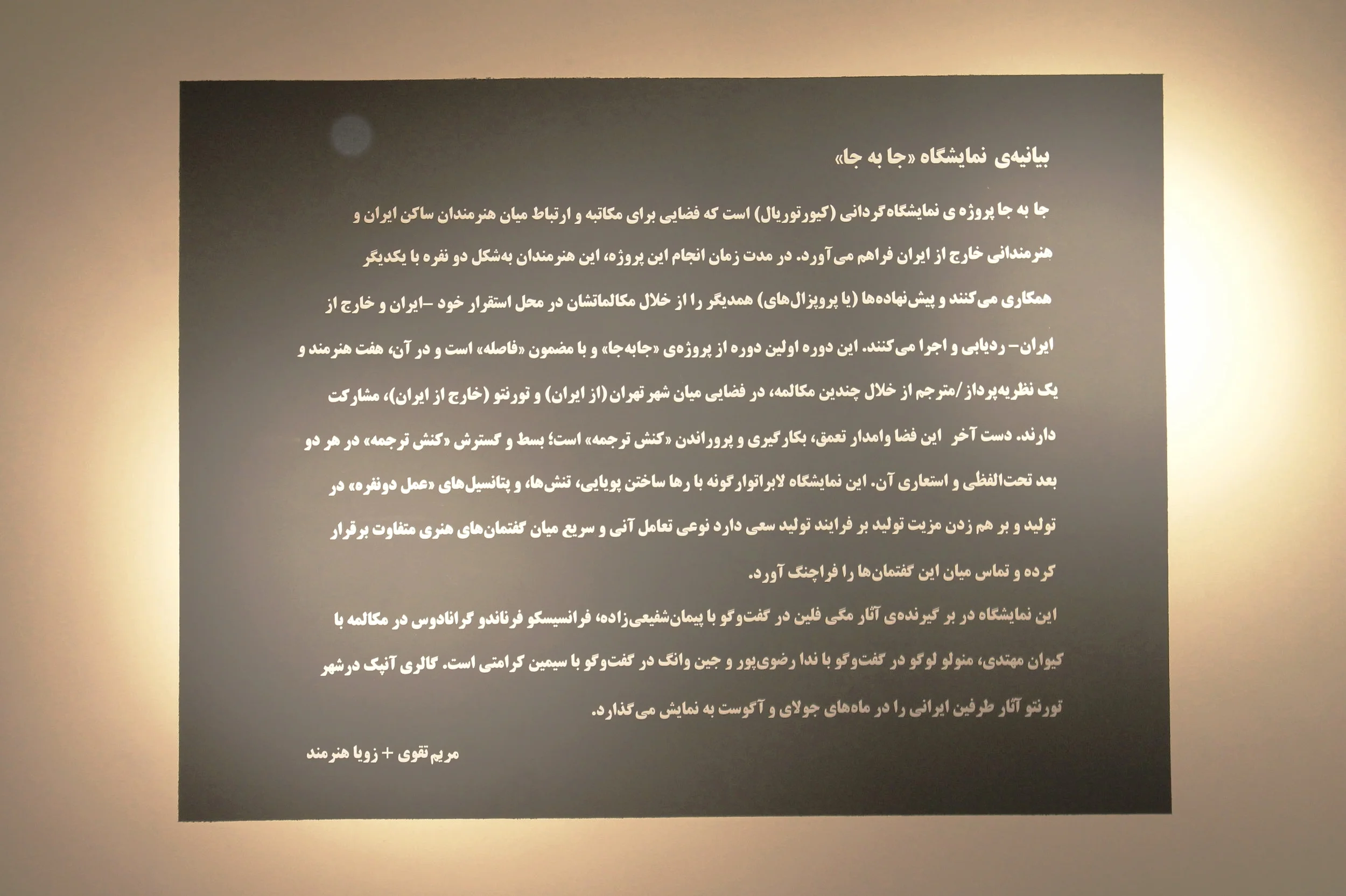

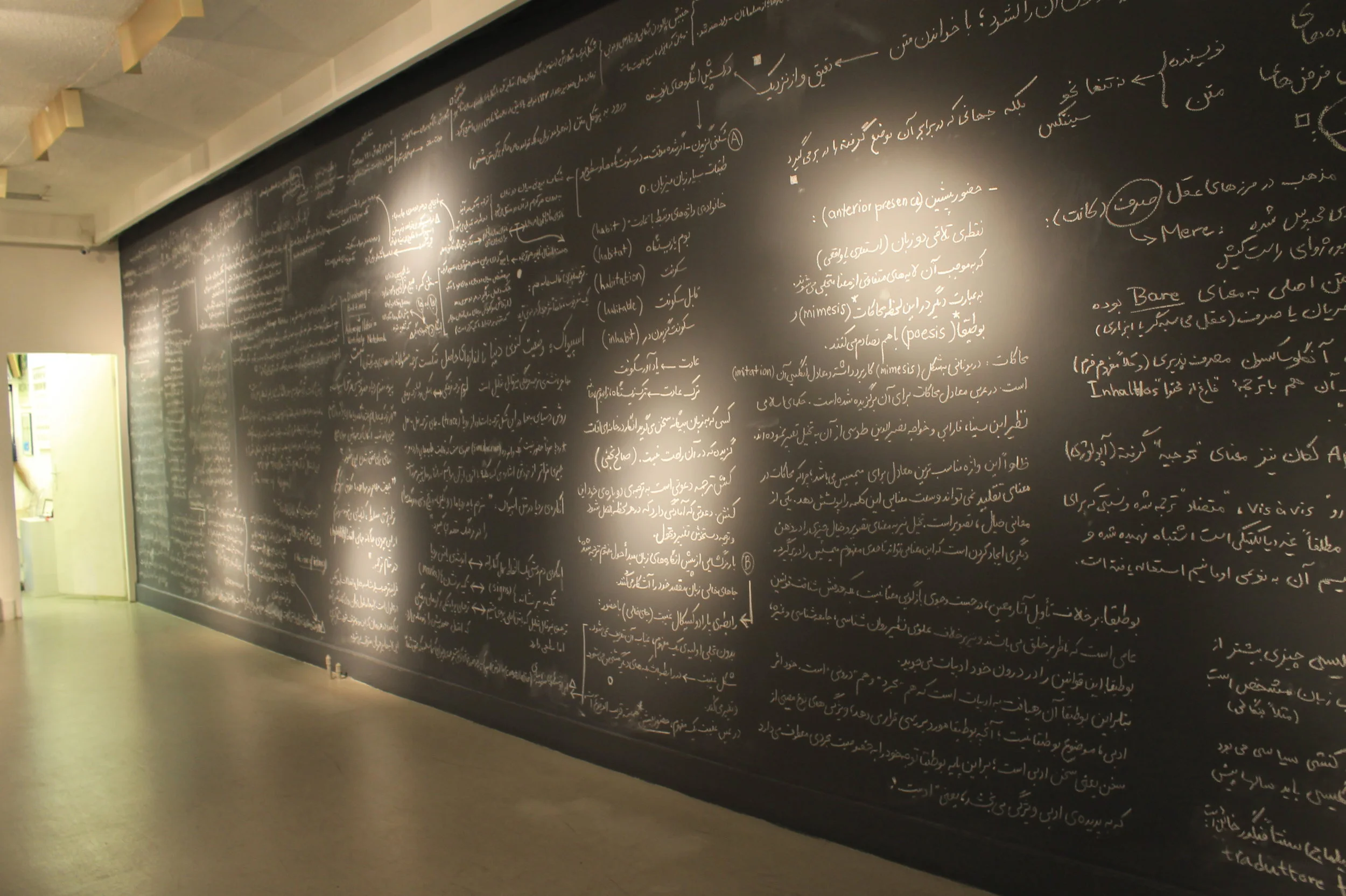

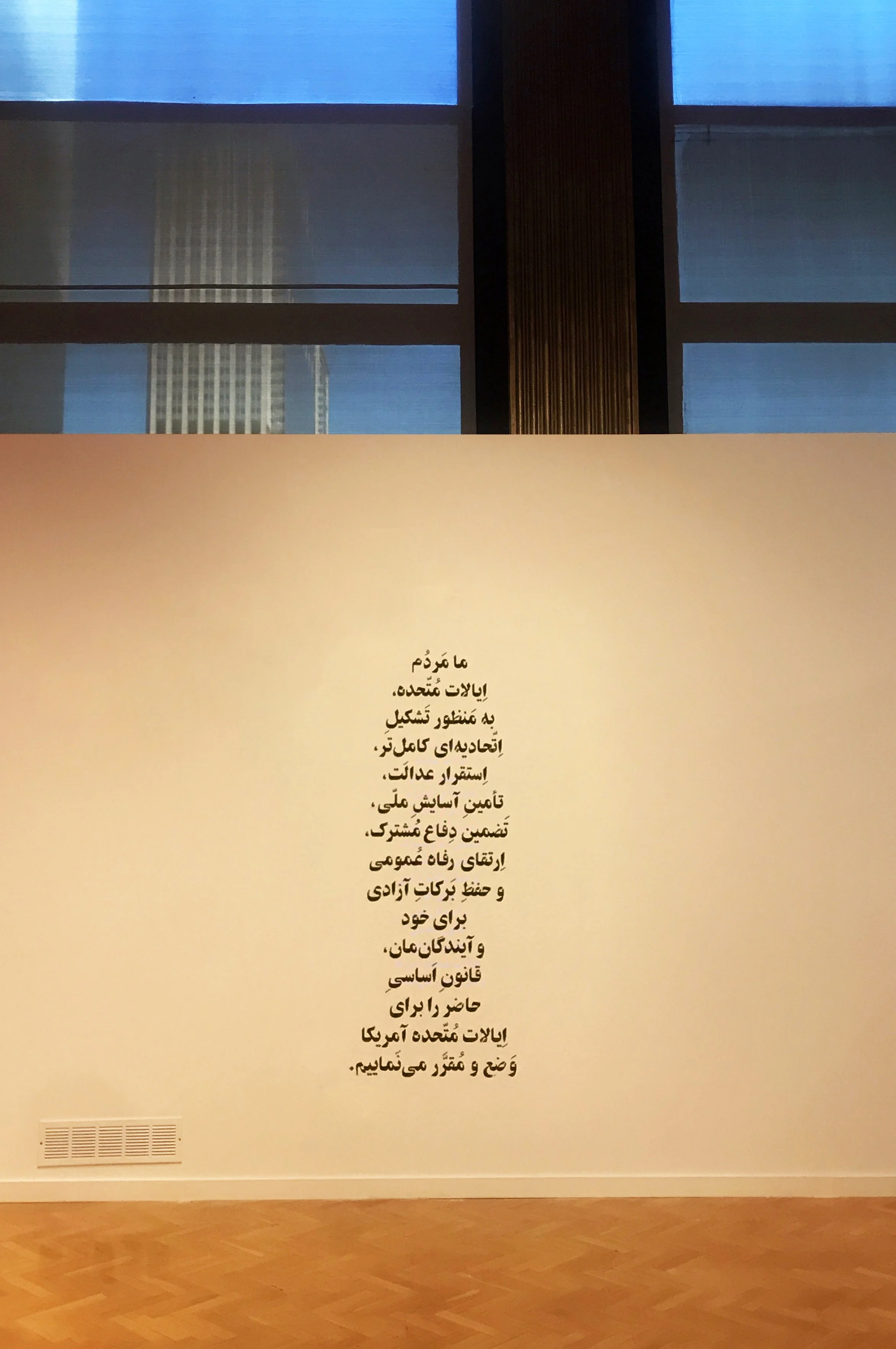

For artist Maryam Taghavi (b. Tehran, Iran; lives in Chicago, IL), the noghte is to literary culture “what the seed is to a tree. It’s impossible to think that this small unit is holding the blueprint for a whole tree, but it’s in there. And I think of the dot or the ‘noghte’ in the same way, that it’s like the entry to a whole world.”[2] In Taghavi’s solo exhibition at the MCA, Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi, the noghte emerges as a central motif that influences both the construction of meaning and how one perceives distance. In the installation, paradoxically titled Nothing Is, Taghavi carefully utilizes elements of a visual culture that she grew up with, such as traditions drawn from Islamic calligraphy, Persian miniature painting, and Persian architecture. Taghavi’s treatment of these traditions is reverential, but it is also subtly irreverent. Using irony, abstraction, and transliteration, her work moves between the transcendental and the transgressive—a transition reflected in the space of the exhibition.

Before visitors enter the exhibition, they are welcomed by a series of cut-outs in the shape of noghte(s) made in the external gallery wall, part of a piece called Quadrilateral view (2023). When visitors peer through this aperture on either side of the wall, they encounter a mirrored prism installed within. This prism houses countless reflections of the noghte motif, a nod to the concept of infinite possibility in Islamic geometric patterns. Here, Taghavi carefully manipulates materials and light to create something that transcends physical constraints to become infinite and, perhaps, magical. Taghavi’s prisms, including this one, are mobile vessels that manifest in different ways each time they are installed in a new space, revealing many versions of infinity.

A second prism, Pentagonal view (2023), is revealed upon entering the exhibition. It is housed within the wall of another work—a site-specific architectural intervention titled Hashti (2023). Designed by Taghavi, the walls of this space form a 12-sided shape, or dodecagon, modeled after a geometric space in Persian architecture. Known as the hashti, this liminal area connects the gate or entrance of a building and the doorway leading to the interior. Traditionally, the hashti serves as a mediator between outside and inside—a place to pause and acknowledge transition.

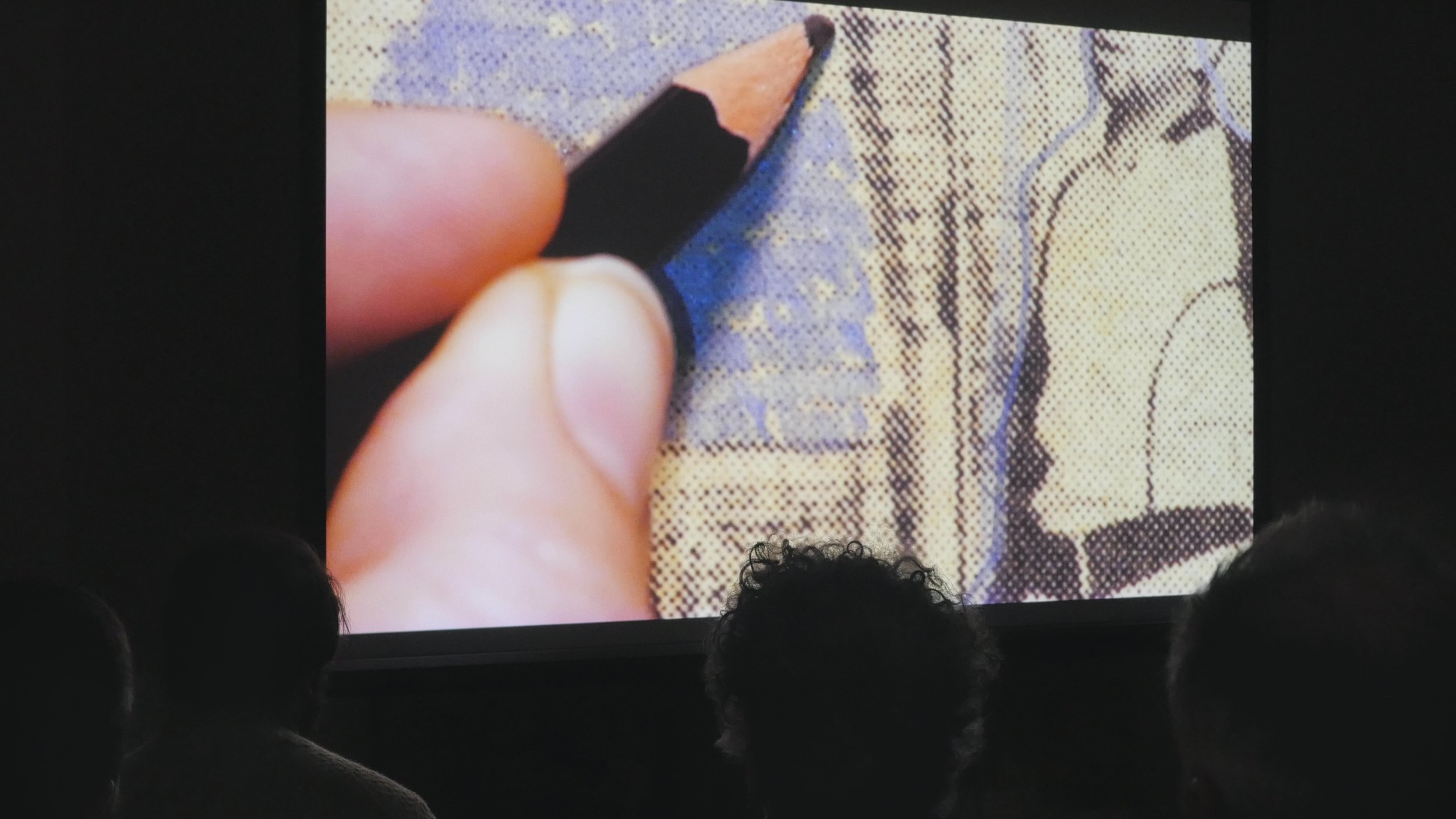

As visitors progress from Hashti into the second gallery, Taghavi decisively pulls back the curtain to offer a glimpse into the innerworkings of her process. She reveals the reality behind her prisms by displaying a third prism, Unfolded Hexagon (2023), unwrapped, or disassembled, on the floor of the gallery, and a fourth, Triangular View (2023), installed as a free-standing sculpture with which visitors can interact. Here, Taghavi affirms the magic inherent to these works—and then purposefully negates it by revealing the illusion.

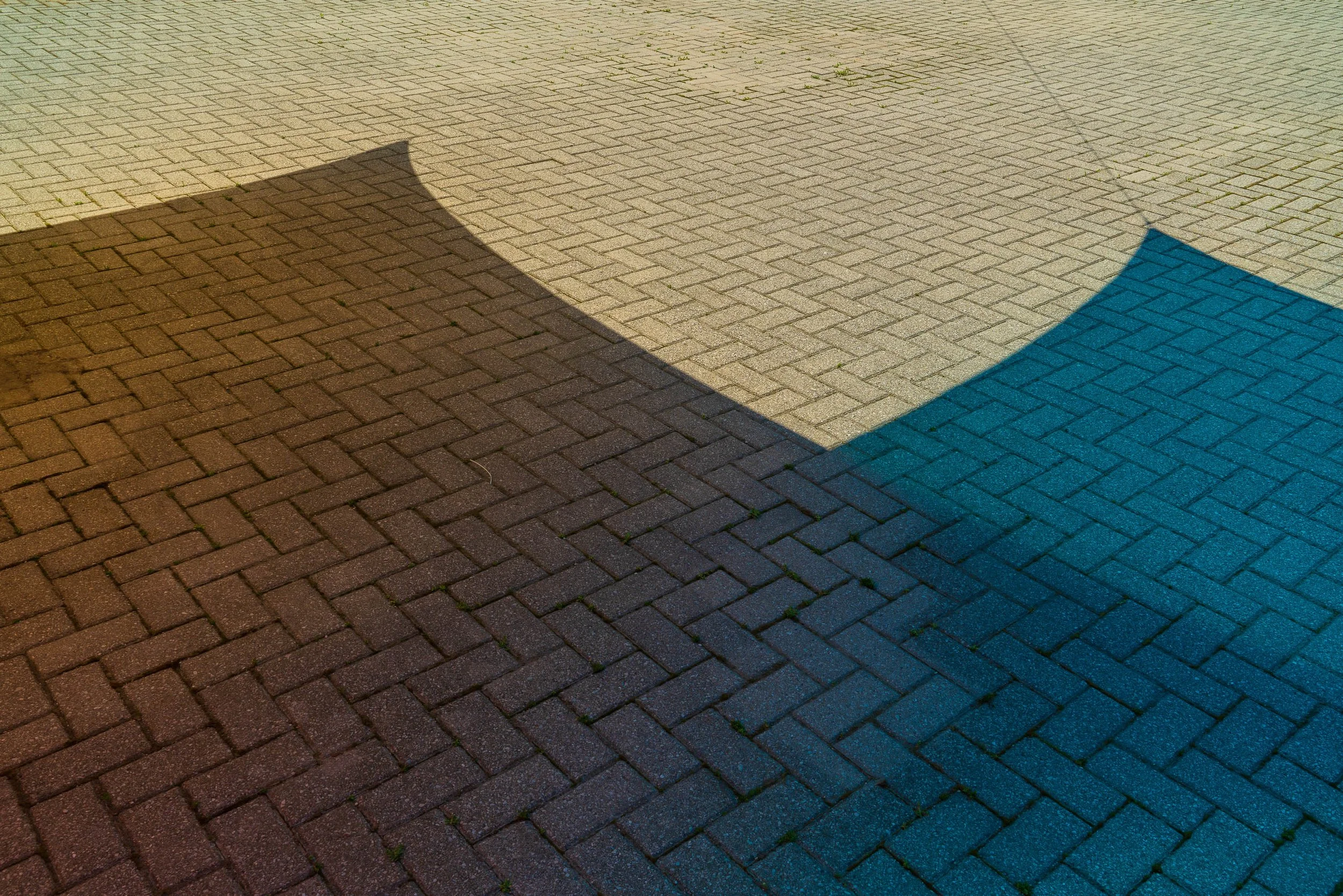

Nearby, six of Taghavi’s paintings from the series Horizon are set against a dark green background. These large-scale, airbrushed works evoke a fragmented horizon, suggested by the familiar noghte, which appears in clusters of three, five, or ten. Taghavi describes the horizon as “the place where the earth meets the sky, an imagined line that our eyes make up, a distance we cannot reach . . . I think there’s something incredibly powerful about that mode of imagination.”[3] Nodding to the noghte’s origins as a form of measurement, these works invite the viewer to consider that uncertain line, and the assumptions their eyes make about its distance.

By pushing back on the viewer’s perception of space, Taghavi’s paintings engage with a longstanding artistic tradition prevalent in Persian miniature painting in which artists flatten the horizon line, thus obscuring the viewer’s depth perception. Historically, Western works of art were governed by the laws of perspective. Three-dimensional space was projected onto a two-dimensional canvas. Artists painted toward a vanishing point to mimic how distance is perceived in real life. While artists in the West concerned themselves with painting reality, Persian miniaturists “presented things as they should be, not necessarily as they are.”[4] Objects in the background were not depicted as being smaller as they moved further from the foreground. Instead, they were placed at the top of the painting, where they remained proportionally the same size as those at the bottom of the painting. The miniaturists’ vertical approach invites the viewer to “perceive space in a more active way,” where “individuals become part of the whole picture, the whole surrounding space.”[5]

As an Iranian artist living in the diaspora for more than 23 years, Taghavi’s practice can also be considered through the postcolonial writings of Homi K. Bhabha. In his book The Location of Culture (1994), Bhabha writes, “The ‘beyond’ is neither a new horizon, nor a leaving behind of the past . . . we find ourselves in the moment of transit where space and time cross to produce complex figures of difference and identity, past and present, inside and outside, inclusion and exclusion.”[6]

In Taghavi’s work, these crossings are both physical and imaginary. To live in the diaspora is to live outside of context. Similar to Taghavi herself, the noghte has been taken out of its literary framework. In the Horizon paintings, the noghte is fragmented, unable to complete the horizon line. It floats in isolation from the letters it ordinarily adorns, allowed only to hold its basic form. In other works, such as within the expanse of the artist’s mirrored prisms, the noghte is liberated, bending and morphing in the light, adjoined to nothing. Again and again in Taghavi’s work, we are asked to use our imaginations. To connect the dots, to dream of the horizon. To face incompleteness, and to exist in the in-between.

In his writing, Bhabha also insists that migrants are active, and not passive, subjects in the transmission of culture—from homeland to host land and back again.[7] This is a useful framework for situating contemporary artists such as Taghavi within a broader, generational shift in Iranian art history identified by scholar Hamid Keshmirshekan. In his essay The Question of Identity vis-à-vis Exoticism in Contemporary Iranian Art (2010), Keshmirshekan describes how many artists working in the 1960s—such as those associated with the Saqqakhaneh movement—incorporated preexisting decorative and traditional motifs related to the ancient, religious, folk, and calligraphic arts in their practice. Their work was identified as especially “Iranian.” While these Saqqakhaneh artists were keenly interested in drawing from Iranian popular culture, those who followed them opposed the use of cultural codes and stereotypes that risked carrying a sense of exoticism into the West. Consequently, over the past two decades a younger generation of artists presented work that featured ironic, kitschy, and sometimes humorous approaches. Through this deconstruction, these artists challenge exoticism, posit a multiplicity of identities, and defy the notion of a singular, unified identity expressed by the previous generation. Yet despite their differences, when compared these two groups share a core concern of collective belonging: where the older generation focuses on national artistic identity by celebrating the traditional, the newer generation challenges the concept of fixed identity through critical and subversive expressions.[8]

Visitors to Taghavi’s exhibition encounter this dynamic in a work titled Heechi (2023). The sculpture is inspired by the artist Parviz Tanavoli, nicknamed the “father of Iranian sculpture,”[9] who pointedly uses source material rooted in Iranian culture and translates it into modernist and abstract forms—such as in his Heech series, which he began in 1965. Referencing both Persian literature and calligraphy, his series uses characters to spell out the Farsi word heech, which translates to “nothing,” a concept used in the Sufi spiritualism of renowned 13th-century poet Mawlana Jalal al-Din Muḥammad Rumi, whose verses explore the concept of nonbeing—not as the termination of being, but as the path to fulfillment and the wholeness of being.

Though Taghavi’s sculpture Heechi is inspired by Tanavoli’s Heech series, she has added a single letter to the word, transforming “heech” into “heechi.” In contrast to “heech,” which represents a nothingness that leads to wholeness and fulfillment, the word “heechi” can be translated into a nothingness that represents emptiness and void. In Taghavi’s words, “that level of divine is removed from it. It’s very much looking down on earth and the everyday . . . [heechi is] the nothing as it appears in life’s disappointments or despair.”[10] If Tanavoli’s Heech series affirms a spiritual tradition, Taghavi uses linguistic slippage and transliteration to question, subvert, and reveal the Heechi. She is not only defying tradition—she is defying an older generation’s fidelity to that tradition, as well as challenging the notion of a fixed identity. “The way of heechi is recognizing my distance to the context where it comes from, to what actually constitutes this idea of perfection and what is profound and spiritual,” she says. “So, I am removing that as a way of recognizing how impossible it may be to hold on to those ideas and thoughts, from where I stand.”[11]

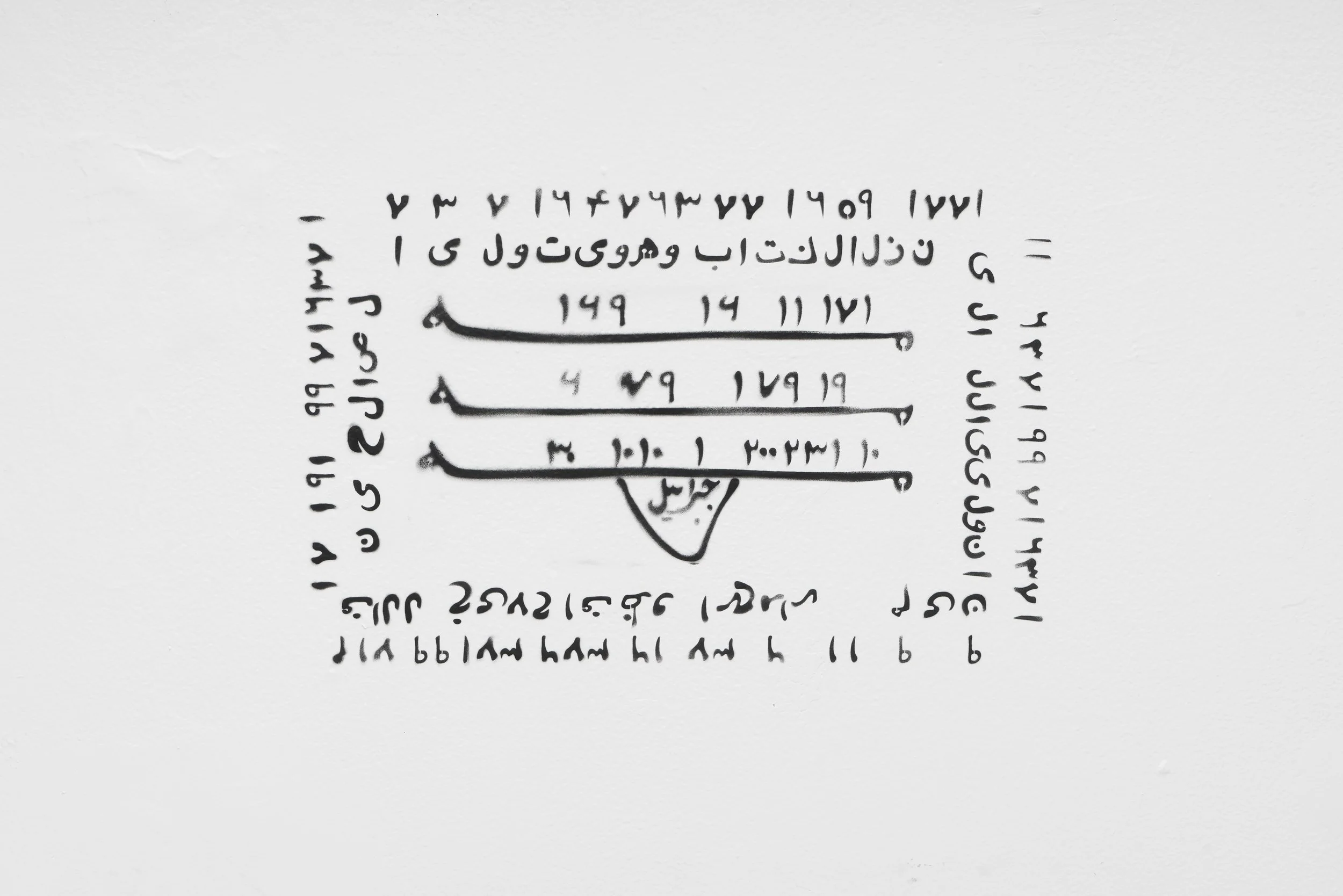

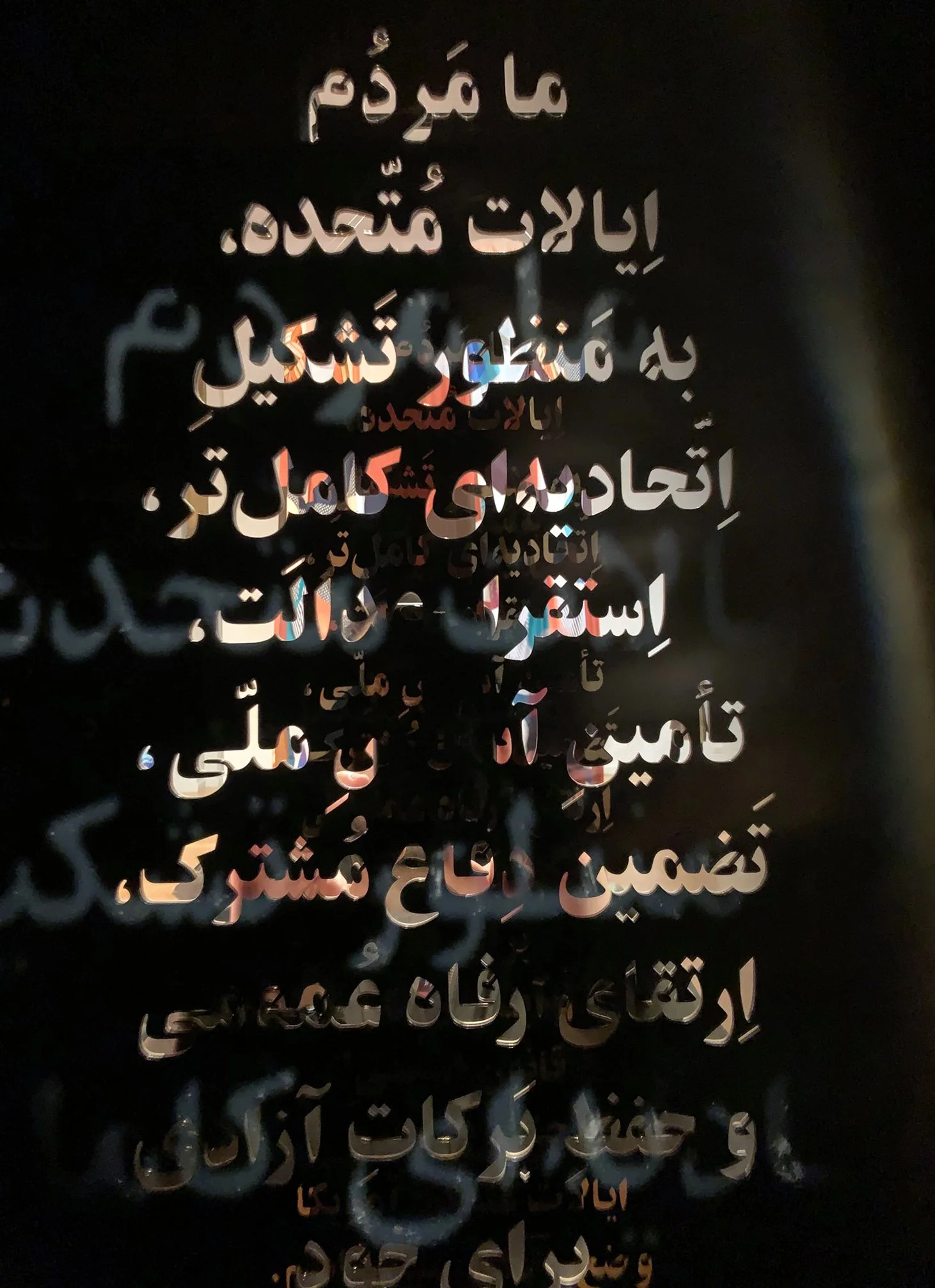

The final work in the exhibition is a small calligraphed text. It is the only work that contains multiple words. To create it, Taghavi commissioned calligrapher Parisa Shafiei to etch an excerpt from a poem [Ghazal #551] by the 13th-century poet Saadi Shīrāzī in a style of calligraphy that is purposefully devoid of noghte(s). Without them, the reader needs to slow down to access the meaning of the text. The poem reflects on the state of longing and the persistence of a beloved’s memory. Elsewhere in the exhibition the noghte refracts through a prism or floats in a painting, separated from the context of letters. Yet here, in Taghavi’s final work, readers experience the inverse: the pure context of letterforms devoid of the noghte(s) that provide their discerning sounds.

In the poem and across her practice, Taghavi uses removal and abstraction to address distance in several forms: spatial, generational, and diasporic. “I am not practicing calligraphy. I am not practicing this perfection,” she says. “I am far away from the context that it comes from. I do have this thread to this language, to this culture, but it’s really hard to preserve it . . . with the distance that I have from it [and] with the time that we are living in.”[12] In Nothing Is, Taghavi asks you to become an active participant in experiencing this distance. If you choose to partake in her choreography of bending, peering, imagining, and connecting, you get to participate in the act of transforming from heech to heechi—materially, conceptually, and experientially.

![ChicagoWorks_[1.8.24]-23.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b4f8c5d1aef1d4328b79153/1707776683501-TZ3UB59S1JSQO1LUT3K7/ChicagoWorks_%5B1.8.24%5D-23.jpg)

![ChicagoWorks_[1.8.24]-21.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b4f8c5d1aef1d4328b79153/1707776679922-SDNUKE11IPLU9KCNZD9Q/ChicagoWorks_%5B1.8.24%5D-21.jpg)

![ChicagoWorks_[1.8.24]-25.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b4f8c5d1aef1d4328b79153/1707776691361-U0DY0M1W1W05ZM6UW0VH/ChicagoWorks_%5B1.8.24%5D-25.jpg)

![ChicagoWorks_[1.8.24]-27.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b4f8c5d1aef1d4328b79153/1707776696629-V6M5IUXZNPFK0T8CALUF/ChicagoWorks_%5B1.8.24%5D-27.jpg)

![ChicagoWorks_[1.8.24]-16.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b4f8c5d1aef1d4328b79153/1707776669688-3ZF0ZBJNG8FLIVJ6F0QC/ChicagoWorks_%5B1.8.24%5D-16.jpg)